City Hall. Pic: Garry Knight

Sadiq Khan’s mayoral election manifesto was filled with promises to reduce air pollution in the capital. He pledged to introduce electric or hydrogen buses for the most polluted routes, create an electric-charging infrastructure and cleaner walking routes for children on their way to school, and put pressure on the government to introduce a diesel vehicle scrappage scheme.

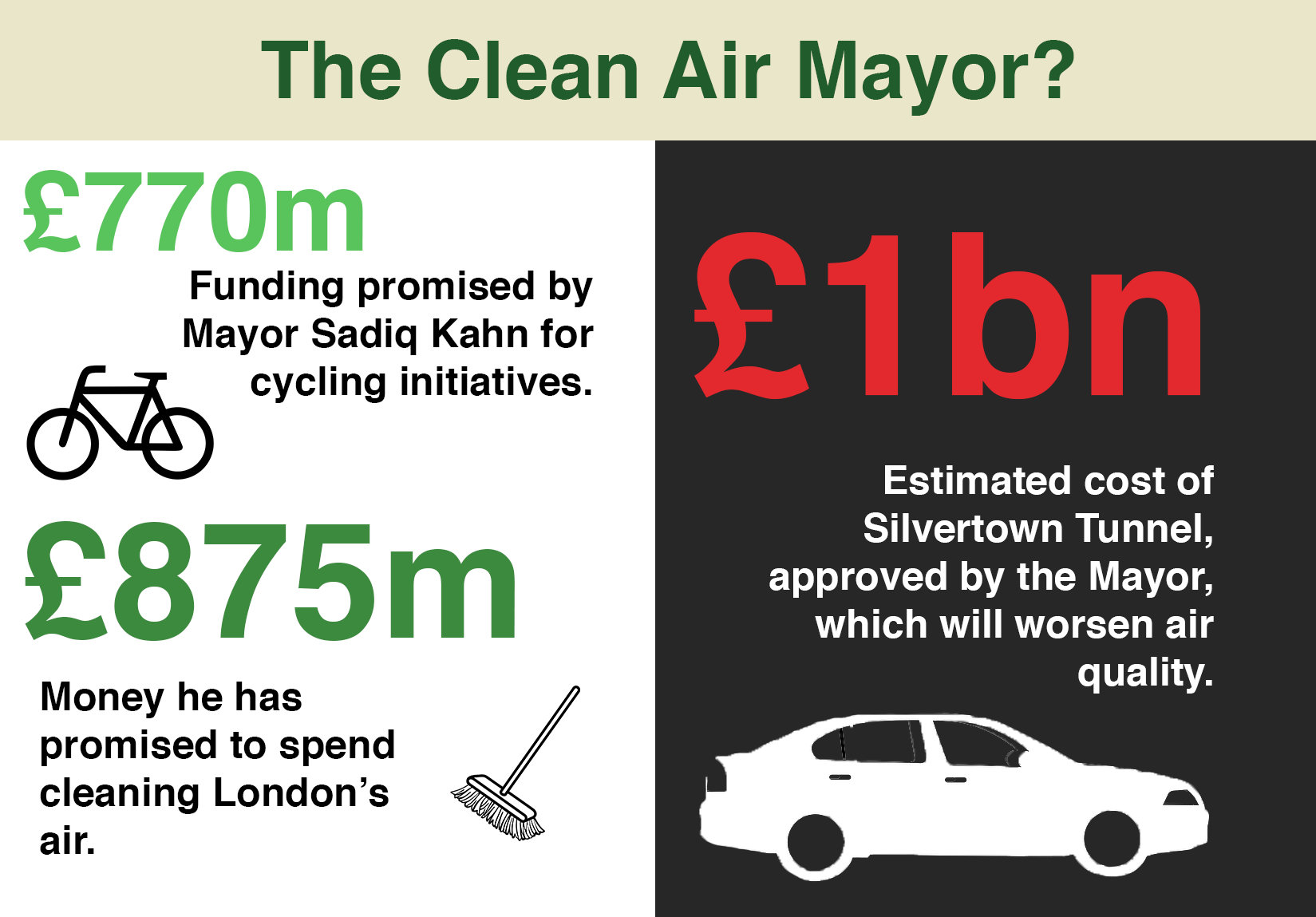

Since winning the election in May 2016, Khan has promised to spend £875 million on cleaning London’s air – over double that of his predecessor Boris Johnson. He’s talking the talk – but is he walking the walk?

What are the mayor’s plans for tackling the smog?

By October of this year, Khan’s Toxicity Charge (T-Charge) will come into action, charging drivers of high polluting vehicles an extra £10 on top of the congestion charge. He also plans to bring forward by a year the implementation of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), a more stringent levy than the T-Charge.

The zone, which will now be enforced by 2019, will extend its boundaries to the North and South circulars as well as place stricter EU emissions standards on all vehicles. Khan has said that buses operating within the zone will meet the Euro VI standards required of them and that all new London buses commissioned from 2018 will be hybrid or zero-emission.

Khan has also provided £6.4 million to 14 local councils to fund their own borough-specific methods of tackling air pollution. As part of this the Neighbourhoods of the Future scheme, which has also received funding from central government, aims to kick off the creation of a city-wide electric charging infrastructure. All no n-electric cars are to be banned from parking off Old Street in Shoreditch, whilst Hackney council is planning to install charging points for electric cars in these areas.

n-electric cars are to be banned from parking off Old Street in Shoreditch, whilst Hackney council is planning to install charging points for electric cars in these areas.

Sadiq Khan has undoubtedly played a key role in raising the profile of air pollution as an issue, as well as acting to reduce its impacts on Londoners’ health. But is it enough?

Have the measures he’s taken so far been tokenistic? Can his pro-business tendencies be reconciled with the need to clean the capital’s air? We look at what other cities have done and propose some important measures Khan needs to take to improve the air we breathe.

Three things Londoners still need from the mayor on air pollution

Stop the Silvertown Tunnel

In October 2016, Sadiq Khan approved the building of the Silvertown tunnel, a four-lane tunnel that will go under the Thames from the Greenwich Peninsula to Royal Docks. Discouraging cars from entering Central London with the T-Charge or the ULEZ make little sense if Khan is to go ahead with the Silvertown Tunnel, which campaigners say will bring more congestion into the capital and increase air pollution levels.

Khan has argued that the tunnel will ‘unlock the massive economic potential of East London’. Campaigners argue that rather than catering to the demands of car drivers, major contributors to air pollution, the mayor should prioritise the health of the residents of East and South East London. The tunnel will cost in the region of £1 billion to build – are there better things we could be doing with the money?

Really prioritising air quality – and tackling climate change – means stopping building major new roads; instead prioritising the health and wellbeing of all Londoners.

A map of the proposed Silvertown tunnel. Photograph: TfL

Copy Nottingham’s car parking levy

In the last fifteen years, the number of car miles driven in Nottingham has decreased by 40 million. Since 2005, there has been a 33% drop in carbon emissions. When almost every other major city in the country has gone in the opposite direction, what has Nottingham done right?

It’s mostly down to high-quality public transport, aided in recent years by the workplace parking levy. Since 2012, Nottingham council have charged employers that who have more than ten parking spaces – as a means to encourage commuters to use public transport. The charge, £375 per year for each space, also earns the council around £9 million per year which the council invests straight back into public transport.

So far, the money has helped fund the expansion of the tram and bus network, as well as renovations to Nottingham railway station. “If you want trams and the biggest fleet of electric buses you have to pay for them,” said Labour Councillor Nick McDonald, a proponent of the scheme within Nottingham council. “The workplace parking levy is the most aggressive way of doing it and the most strategic for the long term.”

A car park. Photograph: heartbeaz

Create a more comprehensive public transport system

So, you make it even more expensive for cars to travel in London (or as Oslo have done, just ban them): what do you do next?

London has a world-class public transport system that far surpasses that of any other city in the UK – but for many people, it still takes too long, is too expensive, and is too crowded. And with London’s population expanding, more investment will be needed.

Cheaper, cleaner public transport with regular and integrated routes covering every corner of Greater London is needed, as well as more extensive and interconnected cycle routes – ambitious yet certainly not impossible demands.

Row of out of service London buses. Photograph: Sludgegulper

Oslo plans to ban all cars from its city centre by 2019, replacing the 35 miles of road previously used for vehicles with bike lanes, as well as greatly increasing its investment in public transport. And in Madrid, as part of a wider initiative to bring daily car usage down significantly, Madrid intend to ban cars from 500 acres of the city centre by 2020 and pedestrianise 24 of the city’s busiest streets.

Or London could learn from Finland’s Kutsuplus – a sort of state-subsidised Uberpool service. Piloted by Helsinki council and aimed at reducing car use, it proved popular with local residents until budget cuts saw it axed. As with Uber, users put their start and end points into an app, which would then aggregate all the destinations – and find the best route to drop everyone at their homes. For those not wanting to walk home from the bus stop on their own, or use their car, it proved a more public-spirited and often cheaper solution. Could London learn from this experiment?

Check out five other unconventional solutions to air pollution from across the globe.

What can I do?

- Join Friends of the Earth’s air pollution campaign.

- Walk, cycle or take public transport – instead of driving.

- Write to your MP about the issue.

Follow our Clear The Air series this week to find out more about the air pollution crisis in our boroughs.