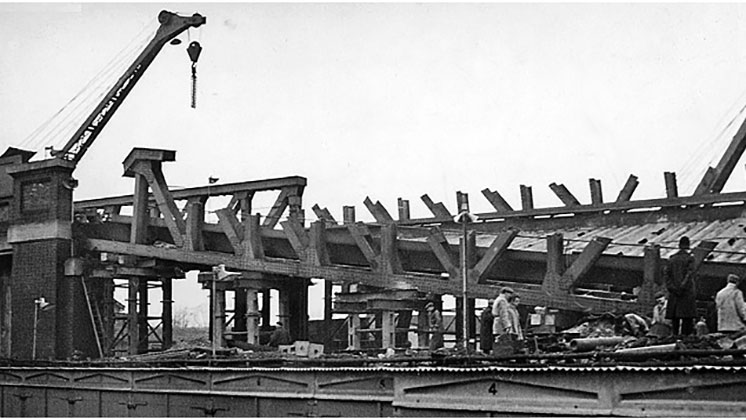

Restoration of St James Bridge Pic: Ben Brooksbank

Sixty years ago today, on a foggy evening on December 4 1957, a steam train collided with an electric train held at a red signal outside St Johns station in Lewisham, resulting in 90 fatalities and 176 injuries.

It was the third worst rail crash in UK history in terms of loss of life after Quintinshill in 1915 and Harrow in 1952.

While the loss of life is still remembered, what is not widely realised was that the accident helped bring about new safety measures which have ensured the safety of millions of rail passengers ever since.

- Pic: Ben Brooksbank

- Pic: Stephen Craven

The Lewisham crash happened when the 5:18pm electric train to Hayes, held at a red signal, was struck by the 4:56pm steam train on its way to Ramsgate. The Ramsgate train was travelling at 30 mph, with the impact of the collision causing the wreckage to strike and dislodge a steel column supporting the bridge, which collapsed. It is one of three major train disasters in the borough, with another two occurring in 1857 and 1967.

The trains carried over 2,000 passengers, with nearly 1,500 on the electric train and about 700 on the steam train.

A report on the collision, published on June 15 1958, stated: “It was inevitable in these circumstances that the casualty list was very great.”

Of the 90 who died, 88 passengers and the guard of the electric train were killed outright and one passenger died later of his injuries.

Pic: Ben Brooksbank

Christian Wolmar, journalist and railway historian, told EastLondonLines: “Steam engines were incredibly heavy and electric trains at the time had very little crash impact resistance. It’s like knocking balsa wood and would inevitably lead to an increase in the number of casualties.”

The primary cause was reported as driver error, with secondary being the dense fog. The driver of the Ramsgate service steam train was later tried for manslaughter but the jury failed to reach a verdict. A retrial was called but cancelled following the driver’s poor mental health. He died a year later.

The collision accelerated the introduction of the Automatic Warning System (AWS) to protect against similar incidents. The Rail Safety and Standards Board defines AWS as “an audible and visual indication of whether the distant signal was clear or at caution. Should the driver fail to respond to a warning indication, an emergency brake application will be initiated.”

Wolmar told ELL: “AWS had been invented in the early 1900s and nobody much took an interest in it despite the fact that disasters from trains going through red signals was not uncommon. There were repeated calls by HM Railways Inspectorate after lots of these accidents to bring in AWS more quickly and they were ignored, largely because the culture was that shit happens basically.

“It became a great scandal that between the 1910s and the 1960s, this system, which is very simple with magnets and a warning, wasn’t introduced. It was a great scandal and it’s not recognised as such.

“It was the same mind-set that led a couple million men to their doom in the first world war, similar numbers in the second world war. If five people get blown up by an IED in Afghanistan, it makes the front pages. It’s all part of that change in culture.”

AWS has since evolved into TPWS, which is a more sophisticated version the safety system. As a result, AWS basically put an end to what were referred to as SPAD – Signals Passed at Danger. Wolmar added: “You need two mistakes to create an accident: the mistake of the driver and the mistake of the AWS. Whereas, without it, one mistake can lead to a major disaster.”

In 2007 on the fiftieth anniversary, Donald Corke, who was driving the Dartford service travelling just behind the collided trains, said in an interview with Kent Online: “As we came on to the bridge, I suddenly noticed the metal girder on the bridge bending upwards towards the carriage.

“I immediately thought the bridge must have fallen down, and applied the brakes. I wasn’t scared, I just had to get on with stopping the train.”

Corke, from Tonbridge, was 29 when he was driving the Dartford Service that evening. He added: “When I looked down over the bridge, the fog was so thick you couldn’t see anything. There wasn’t a sound coming from the wreck – you could hear a pin drop.”

In 2003, Corke unveiled the plaque outside Lewisham train station commemorating the tragedy.

I was in the first coach of the steam train and survived with slight injuries even though it took three hours ot get me out…. Richard Graham

Many accounts of this accident claim that Driver Trew ‘died a year later’, ‘a broken man’, etc.. There is no official record of this. My research (for my upcoming book on accidents in SE England) shows that William John Trew of Ramsgate was born in 1896, was 61 at the time of the accident and died in 1970 in Ramsgate.