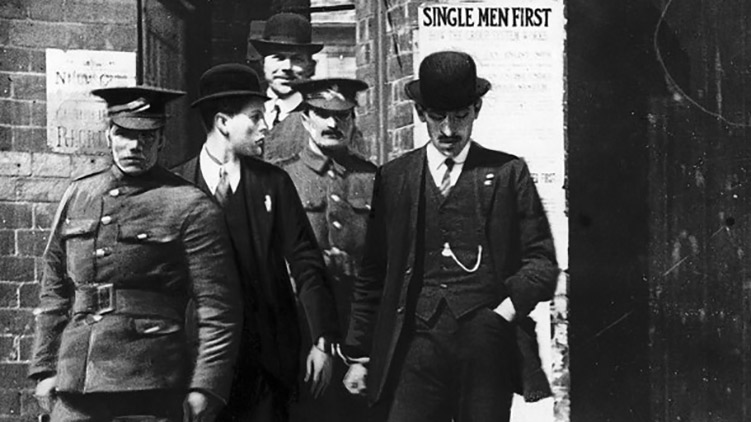

Picture: Mirrorpix/UIG

The introduction of conscription, 18 months into the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, gave rise to an unprecedented problem for the British government – the Conscientious Objectors. Labelled as “conchies”, the men came from all backgrounds. Sometimes, their reasons for asking to be excluded from military service were tenuous excuses, but most were driven by their unswerving conscience.

Although conscription was quite common, the British military had been able to fight the war without it until March 1916. Despite an active voluntary recruitment programme, conscription was eventually deemed a requirement for military victory. To some, this method of raising troops was inconsistent with their national character and liberties. Eventually, the Cabinet authorised a “clean cut”, whereby physically fit men between eighteen and forty years of age, irrespective of occupation, were made available for the forces.

However, it was not only civilians who were coming forward with their moral, religious and political objections. The practice became increasingly common even among men serving in the army, who had witnessed first-hand the devastation caused by war. The task of classifying these individuals caused much distress.

[masterslider alias=”ww1-conscientious-objectors”]

Click on the arrow at the right hand side of the image above to scroll through our slideshow.

In the First World War, there were about 20,000 conscientious objectors. Some of them regarded themselves as “Absolutists”, refusing to cause harm to any other man. They were typically associated with religious stances, such as the members of the Christian church or Quakers (formerly known as the Religious Society of Friends) and were strictly against the idea of partaking in any activities supporting the war. Others were termed as “Alternatists”, and had agreed to serve in non-combatant posts. Tribunals, comprising of local figures and military representatives, were hastily set up to deal with the fate of these men.

It was in the four boroughs of Lewisham, Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Croydon, that many conscientious objectors would face these tribunals. The Croydon tribunal held its first sitting on February 29, 1916. In the three years of war, they had dealt with 10,445 cases and granted merely 2,901 exemptions. Additionally, Croydon also had in place a second tribunal known as the Coulsdon and Purley tribunal. The borough of Lewisham had two separate tribunals catering to objectors from Catford and Deptford, as they were separate boroughs at the time. Most records were destroyed after the war; however, the council has been able to retrieve information about 113 individual cases from the borough. Around 350 conscientious objectors are known to have lived in the London Borough of Hackney.

Being a conscientious objector brought with it many hardships and avoiding the war did not come with an easy lifestyle. Some might even argue that it required more courage to stand up against public opinion, due to the unpopularity and persecution that followed. The objectors were regularly subjected to severe forms of intimidation – backbreaking physical labour, exposure to harsh weather conditions, solitary confinement and mistreatment from prison guards – in an effort to unnerve their staunch principles. Even the media’s attitude towards the men was rather hostile; however, they did become more concerned with the treatment meted out to the prisoners during the later years.

According to the No Conscription Fellowship, 6312 men were arrested for resisting service. More than 800 men served jail sentences beyond two years. 73 men died after their arrest.

Colossal personal pressures were inflicted on the men, not just by the state, but also by communities, friends, and even families. There were numerous instances where communities were shred apart, and men were shunned by their families who could not be reconciled with even after the war. The obsession with equal sacrifice led to the stigma of having been a “conchie” materialise in the form of bars to promotion, even to employment itself, and all conscientious objectors were open to discrimination if their absence of war records became public. Furthermore, they were also disqualified from voting in national and local elections for five years after the end of the war. It was not surprising that some even preferred to leave the country and start afresh.

Illustrated here are two particularly interesting stories of conscientious objectors from the ELL boroughs- Charles John Cobb, a 38-year-old ‘Absolutist’ from Croydon, and 18-year old Dave Cherlyn from Hackney for whom things took a rather surprising turn for the worse.

Follow the link to read more about WW1 in ELL boroughs: