Every wedding is different. Same-sex marriages, though, seem to be linked by one common theme. They are all, still, inherently political. Here, three local couples tell us their stories: the trials and tribulations, the laughter and tears that led up to their special day.

‘Queer Love is Magic’: Charlotte and Catriona

“Queer Love is Magic”, reads the banner draped across Charlotte Harris and Catriona Knox’s living room in Stratford. This sums up how Harris and Knox feel about their own marriage. “It’s about radical love,” Harris says. “Even though great strides have been taken, marriage still feels like a radical thing to do. It is something that has been denied to us, we have to make it our own.”

Actress and writer Knox agrees, “That’s the brilliant thing about queer weddings. You can totally reframe them. You don’t have to be penned in by expectations.”

While Harris and Knox’s interpretation of marriage is unconventional, their meeting followed a more familiar route, meeting through a mutual friend at the Queen Adelaide pub in Bethnal Green in 2017. “I was having a drink with my friend Jamie,” says landscape designer, Harris, “When he told me ‘My friend is meeting us’, I was quite cross, but then when Catriona walked through the door. Everything changed! It probably was love at first sight.” The feeling was mutual. “I headed off with Jamie after meeting Charlotte. I remember saying ‘Charlotte seems really nice’,” says Knox.

The two then bumped into each other again at Pride and started dating soon after. Harris, 48, proposed to Knox, who is 38, in April 2019 while on holiday in Llandudno. It was a proposal Harris had planned long in advance. “The ring had been in my pocket for months,” says Harris, “but I couldn’t find the right moment to propose. When we were on Llandudno pier and it was an incredibly warm weekend, I knew this was the right moment.”

After having to postpone their wedding for two years due to the pandemic, Harris and Knox finally married on Bonfire night in 2022 at New Unity in Newington Green. The couple felt the Unitarian church perfectly matched their vision for their wedding. Harris says, “I really like what New Unity stands for and its values. I think that queer marriage is political, so it felt important to be in a political space.”

Both women danced down the aisle to Olivia Newton-John’s Xanadu and the service included an acknowledgement of the generations of LGBTQ+ people who couldn’t marry. “We had lots of cheering and it was really joyous,” Harris says. “I was completely elated all day. I felt genuinely carried by all the love,” says Knox.

Reflecting on ten years of marriage equality, Harris and Knox agreed that visibility is key to changing attitudes, using their own wedding as an example. Harris says, “We had friends and relatives who had never been to a queer wedding before. I think it really challenged people’s preconceptions. She says, “There were older relatives sat having dinner with people who use different pronouns and I think they realised it’s not this terrible thing.”

“Representation is equally important. I think that by seeing gay marriage you can understand it more,” Knox says. Harris adds, “I grew up during Section 28 and you had such an anti-queer culture and politics, if I had been 11-years-old seeing a queer marriage on screen that would have been life-changing.” Harris says, “For younger people, you can make a better experience and make them more comfortable with who they are.”

‘We tried to play it down’: Martin and David

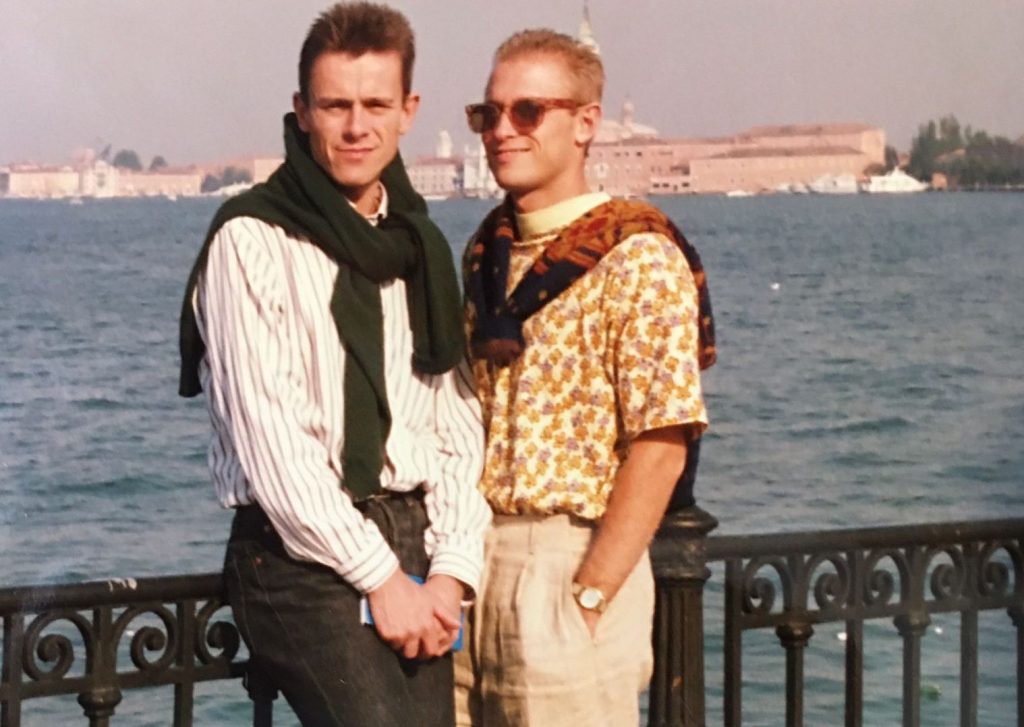

In 1982, Martin walked into the Star Garter pub looking for an excuse to leave: “Ah there is nobody here, let’s go,” he said to the friend accompanying him. His friend insisted they stay, so Martin sat in the corner without saying a word. As fate would have it, David walked over, the first person Martin met as an openly gay man. The same man Martin has spent the last 40 years of his life with.

A month before, a 21-year-old Martin had just come out for the first time – to the same friend who forced him into the Star Garter. “She pushed me to tell her,” he says; the friend responded by saying, “Fantastic, in that case, we’re going to the gay society pub in a month’s time.”

When they arrived at the Star Garter his friend insisted she bring a man over to the table. “Of course, I knew,” he says, but the younger, shyer Martin told his friend, “just one of those two over there”. Fortunately, Martin’s friend chose well.

“He just seemed like a nice, friendly and warm man,” Martin says about his now-husband, David. “I am sure David would say the same about me.”

Today, Martin, 62, is a retired analyst relations executive. He now works as an anonymous volunteer at an LGBT+ charity, and so asks we use his first name only. He lives happily with David, 63, in the same house they bought together in Hackney Wick back in 1989.

During their early time together, Martin says queer culture placed a high value on sexual freedom. As a gay man or lesbian during the 1980s there was no option to get married, so they adapted, he says: “You just had to enjoy it.”

“We were told in queer magazines that if you were monogamous, you weren’t gay. If you were in a relationship, you were ‘not free’.” Martin’s reaction was to say, “Well, I want a partner, I want to be in a relationship. That’s what I want! I was a relationship person.”

So, going against the prevailing queer culture at the time, Martin and David moved in together in 1985, into their new home in Stoke Newington.

Martin says that being with his husband before the Marriage Act passed was, in some ways, a blessing. “There was this freedom,” he says, “of not having this expectation of something that society says you should do. We could just get on with it.”

But of course, in the 1980s and 1990s, it wasn’t just the freedom that defined queer culture or their same-sex relationship. The threat of AIDS could not “be taken out of my generation’s fear,” says Martin, “I lost five of my closest friends.”

Martin remembers fearing for David’s life, before it was known how AIDS was contracted: “He’d get a cold, you’d think, ‘that’s the pneumonia’. He’d get a mark on his leg, you’d think, ‘that’s the Kaposi’s sarcoma’. Every little thing, you just feared.”

Into the new millennium, though, there was much more cause for celebration. In 2005, Martin and David were able to enter into a civil partnership. And then, of course, in 2013 they were finally able to contemplate marriage.

At first, Martin says he was indifferent about the thought of marrying David. But then, he saw “the protests and anger in the public” when the Marriage Act was proposed by the Conservative Party. That, he says, made him realise, “Absolutely, 100% we needed to get the same legal terms as everyone else.” And, in the end, it was the political meaning behind his marriage, more than anything else, that was “hugely important”.

In 2014, Martin and his husband went for, what was supposed to be, a low-key lunch in the middle of the week to “play it down.” But, he says, “the response of all the people that came was just so overwhelmingly happy and joyful to celebrate with us.”

Overall, “playing it down” seems to have led to a lot of joy in David and Martin’s relationship. Martin says the secret to having a happy marriage is to “try and stop yourself from having expectations. Just stay in the moment.”

‘Having a Jewish wedding was important to us’: Rob and Omar

For Rob Freudenthal, 36, and Omar Portillo, 42, getting married in a Synagogue was important. For Freudenthal, marriage was not only a union between himself and Portillo, but brought together his identities: “As a Jewish person and a gay person, we are used to fragmenting our lives somewhat being from different minority groups. You often have to compartmentalise your Jewish life and your gay life.” He adds. “It felt meaningful to be able to do it in that way.”

The couple live in Stoke Newington, Freudenthal is a psychiatrist and Portillo is a social worker from Honduras who grew up in New York City. The couple met by chance in a bar in New York City in 2013, while Freudenthal was on a trip there. They hit it off immediately and started a long-distance relationship until 2014, when Portillo moved in with Freudenthal.

Soon after, the couple started to explore the possibility of marriage. “We decided it was something we wanted to pursue,” Freudenthal says. The right moment to pop the question came during a 2015 holiday in Rome.

Portillo converted to Judaism, and the couple married at Kehillah North London in 2016. “It felt really special to have a Jewish wedding, it was important for us as a couple to do,” Freudenthal says. “Through having a Jewish wedding, we had to think a lot about our relationship with Judaism with its rituals and traditions but also what we wanted to celebrate in the wedding.”

Marrying at Kehillah North London allowed them to have a traditional Jewish wedding in a slightly less traditional Synagogue. “We had a relatively traditional wedding with, for example, the breaking of the glass which felt like a meaningful thing to do. But the Rabbi who married us is a lesbian and her partner played the music. So she really understood our wedding,” says Freudenthal.

Since their wedding, Freudenthal and Portillo have become heavily involved with Kehillah North London, where Freudenthal is now Co-Chair. Freudenthal says, “It’s a Synagogue with a diverse community with other gay and lesbian couples; it felt like a community we wanted to be a part of.”

Reflecting on 10 years of marriage equality, Freudenthal admits that if religious same-sex weddings were not permitted and the couple had to marry in a civil ceremony, he would feel something would’ve been missing. “It wouldn’t have been as useful for my and my husband’s personal growth,” Freudenthal says. “We joined the Synagogue in part because we wanted to get married there and now we’re very involved with the community. So our wedding was a stepping stone in that sense.”

Freudenthal has noticed changes in people’s attitudes to same-sex couples since marriage equality. He described this as “a very positive and huge shift in a relatively short space of time.” He used his own experience as a Jewish man as an example. “My Mother is Orthodox and they wouldn’t do same-sex weddings. She did organise a Kiddush (a Jewish celebration with food and wine after a service) for our wedding at her Synagogue.”

“That was definitely something that would never have happened when I was a child and it really feels like things have changed in terms of acceptance.”

A decade may have passed since their normalisation was enshrined in law, but same-sex weddings are still deeply meaningful. If you have a story to share about your own same-sex marriage, we’d love to hear from you: get in touch via Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tiktok or email us at news@eastlondonlines.co.uk.

This article is part of our series, A decade since ‘I do’: celebrating same-sex marriage in London, click here to read our other stories.